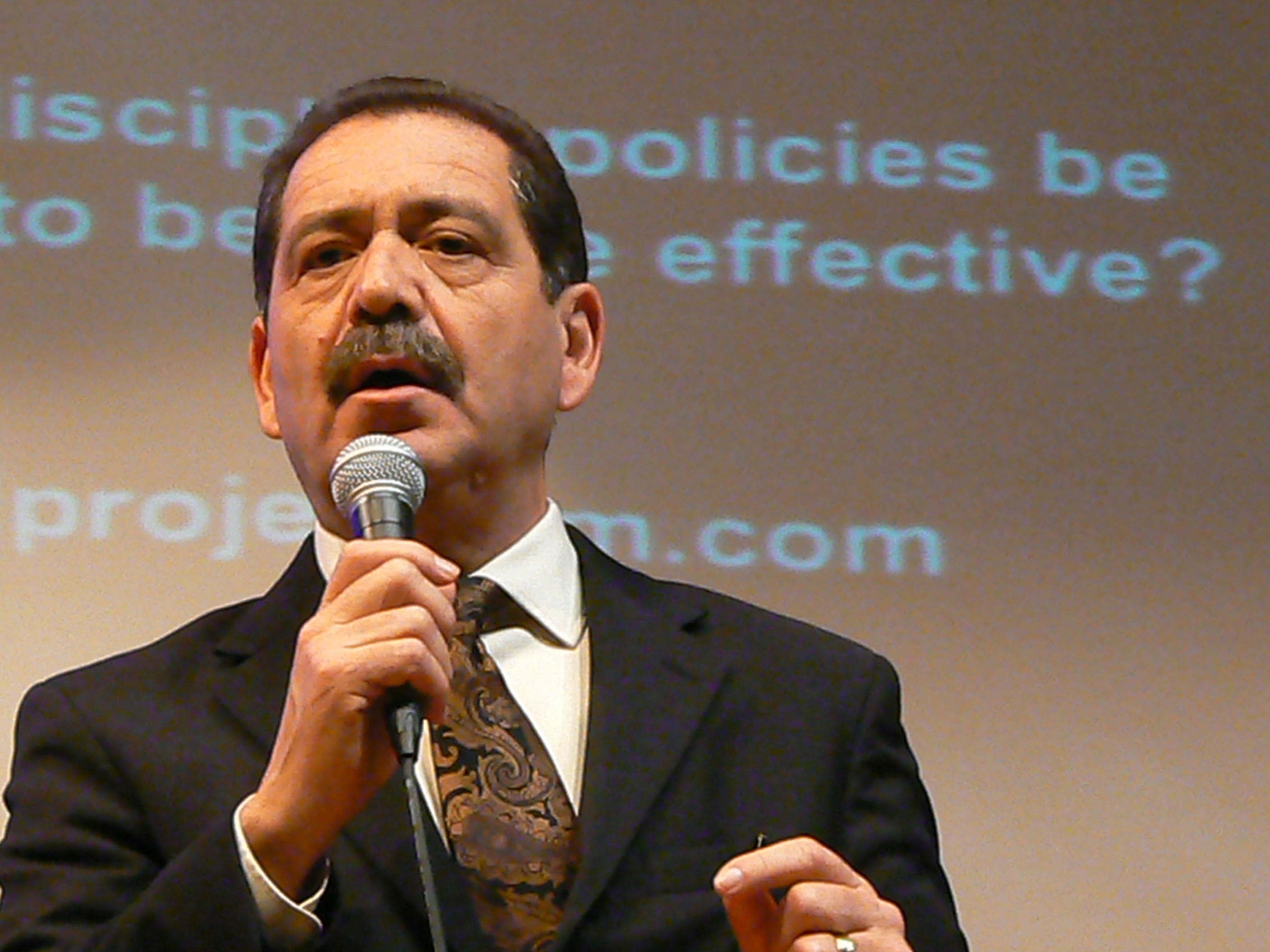

Mayoral candidate Chuy Garcia speaks at event in North Lawndale

By La Risa Lynch

Mayoral candidate Jesus “Chuy” Garcia supports increasing more restorative justice program within Chicago Public Schools as a way to “create good healthy communities.”

Current discipline policies, he said, fuel the school-to-prison pipeline that disproportionately affects minority youths. Garcia added whether the school-to-prison pipeline is intentional or not, “it is structural and we need to stop it. We need to break it.”

“Unless we are able to do those things we continue with discipline policies that profile, that target, that expel and only exacerbate conditions of inequality in our communities…,” Garcia said.

Garcia appeared at a March 5th film screening and panel discussion on the student produced documentary “Restoring Justice – Chicago’s School to Prison Pipeline.” The screening was shown to a pack auditorium in North Lawndale College Prep High school, 1313 S. Sacramento Ave. Event organizers invited both mayoral candidates to speak.

The documentary, done by students from Free Spirit Media, examines school policies that excessively punish students for minor infractions often resulting in suspensions and the criminalization of youths. It also examines the grassroots movement to have school leadership adopt restorative justice practices.

According to February 2014 CPS report on suspensions and expulsions, 69,845 students received out-of-school suspensions district wide for the 2012-2013 school year. While Black students comprise 41 percent of CPS student population, they account for 75 percent of all suspensions.

Since 2012, CPS has begun retooling policies to limit out-of-schools suspensions by developing restorative justice approaches that keep students in schools. As a result CPS has seen a 36 percent drop in high school suspensions since the 2010-2011 school year.

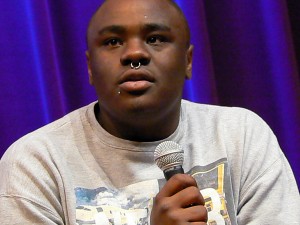

CPS has made strides to reduce suspension through restorative justice programs, but panelist Quabeeny Daniels questioned the militarized atmosphere in some of CPS schools. Some schools have in-school police officers that a report by Project Nia found in 2010, 20 percent of all juvenile arrests in Chicago occurred on school property.

“When I was in school I felt very militarized,” the Gage Park High School graduate said. “I felt like we had to stand up straight, walk in a line, put our fingers over our mouths so we don’t say anything even at lunch. I feel like that pushes us out of school more. A lot of my friends have not returned to school after they have been expelled or suspended.”

Steinmetz High School senior Dalia Mena agreed. She said metal detectors in schools add to the atmosphere. She recalled a time when she had a Snapple bottle in her backpack and had to report to the in-school police department to have her bag search “because I had a glass bottle.”

“For me I feel like I am in a prison,” said Mena, a youth leader with Voices of Youth in Chicago Education (VOYCE). “Why do you have to check through my things? That’s not right.”

Students, she added, need to be given more credit that they are not always doing something wrong.

Daniels added that youth are not giving the space to talk about what’s going on with them in school. Youths, he added feel criminalized when told by teachers and parents they are not going to be anything.

“That sticks with us,” said Daniels, who works for Mikva Challenge, program that empowers youths to become civically and politically engaged.

However Mena did applaud CPS for adopting restorative justices programs, like peer juries. She said such programs should be in all schools, not just a few. Efforts to start a restorative justice program at her school were thwarted by school administration. But she added there needs to be consistent and effective training for students, teachers and administrators to ensure success.

However Mena did applaud CPS for adopting restorative justices programs, like peer juries. She said such programs should be in all schools, not just a few. Efforts to start a restorative justice program at her school were thwarted by school administration. But she added there needs to be consistent and effective training for students, teachers and administrators to ensure success.

CPS is making investment around restorative justice training said Karen VanAusdal, CPS’s office of social and emotional learning director. That, she said, includes teaching students social and emotional skills “so when they are in a peer jury or a peace circle they have the capacity to listen to one another and to empathize,” to be effective restorative justice practitioners.

Social activist Mariame Kaba noted CPS use of restorative justice practices came after years of grassroots advocacy to rid language around “zero tolerance” policies. But the concern now is the disproportionate number of Black students still impacted by suspensions, she said.

“The percentage of people being suspended remains Black youth,” said Kaba, founder of Project Nia, a grassroots organization fighting to end youth incarceration. “The people being arrested in our schools 80 percent are Black kids.”

She contributes that disproportional contact to a pervasive anti-Black culture in America compounded by a punitive culture. That sentiment bubbled to the surface by events in Ferguson, MO. and New York. In both instances Black men were killed by white police officers.

Kaba said she doesn’t want to see any student regardless of race arrested or suspended. But the data shows who’s actually “being targeted by these kinds of policies,” and that is Black youth.

“If we do that we can at lease actually have a real conversation about what needs to be done to change it,” Kaba said.

The film, “Restoring Justice,” is part of a six part documentary series called The School Project. The project uses interactive maps, documentary videos and news coverage to examine public education policy in Chicago.

Skyler Dees, who worked as a pro-producer for the documentary, hoped it demonstrates that the school-to-prison pipeline is an “actual thing.”

“It is something that affects students whether they realize it or not…,” said Dees, whose been with Free Spirit Media for nine years and works as a chef at A Safe Haven Foundation’s catering service. “Punitive policies are retaliation against students. That’s the reason why restorative justice is pushed as a philosophy because it is a needed change.”

Restorative justice is just one tool Garcia wants to use to address public safety. He also wants to put 1,000 more cops on the street to strengthen community policing, which Garcia said “goes hand in hand with restorative justice.” He said these officers would work to build trust and mutual respect among residents so they can work together to reduce crime.

But Kaba disagrees.

“A 1,000 new cops are not going to make us safer,” she said. “We are seeing that in many of our communities. They exacerbate a lot of the issues going on now. Having police in schools is a negative on a regular basis. I deal with young people pushed out [of schools] because they are arrested by police within schools. I think we cannot have that as our main strategy for public safety.”

Be the first to comment on "School-to-prison pipeline examined in student produced film"