By La Risa Lynch

It became a symbol for Black power and pride.

But the black-gloved fist salute John Carlos and teammate Tommie Smith gave on the medals stand at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City almost didn’t happen.

The Olympics became a stage for Carlos and Smith to make a political statement for civil rights when they took the medals stand after winning bronze and gold respectively in 200-meter dash.

When Carlos and Smith stood on the podium, both raised a black-gloved fist in defiant protest to highlight the struggles of Blacks for equal rights, not just at the ballot box and public accommodation but also in college sports programs.

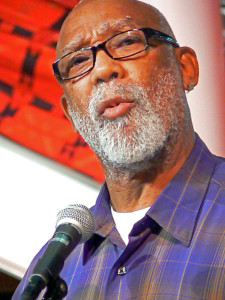

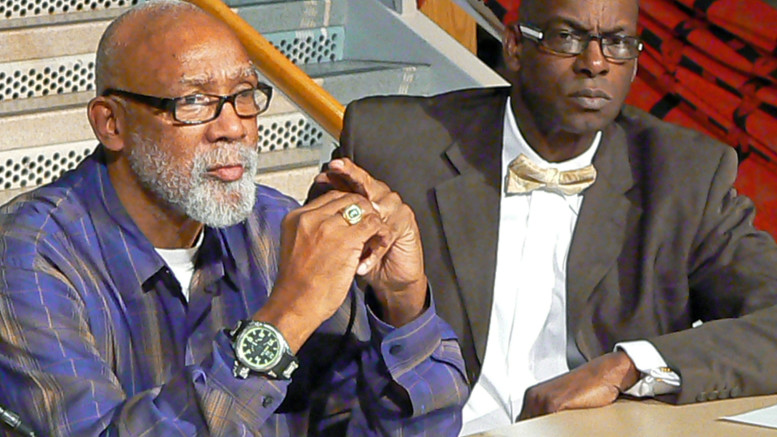

1968 Summer Olympian John Carlos speaks at a Black History event at Chicago State University about his now-famous black glove-salute during the Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

“As young athletes we thought we could make a difference,” said Carlos, who keynoted a Black History event at Chicago State University. “We felt that we would be a little more in sync with one another across the board, but we found that not to be true.”

That prolific symbol of Black solidarity played out differently behind the scenes. A Black athletes group called the Olympic Project for Human Rights began calling for the boycott nearly three years before the 1968 Games. Anger within the Black community about the assassination of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Robert F. Kennedy still smoldered.

Carlos, who knew Malcolm X personally, felt a boycott would send a message about racial injustice without “throwing a rock, firing a bullet, not even throwing a punch.”

But the “feds,” were leaning hard on some Black athletes not to protest the Games. Athletes, he added, had to decide whether they wanted to win medals or sacrifice that for a cause.

“That’s the way they divide and conquer,” Carlos said. “You were in the greatest Olympics of all time and you had an opportunity to make a difference for society — more so, for your own race, and you … chose not to do anything.”

Carlos said he has no hard feelings for those athletes, but he added not everyone is cut out to be an activist.

“Nobody wants to be an activist,” he said. “Dr. King didn’t want to be an activist. Rosa Parks didn’t want to be an activist. Marcus Garvey didn’t want to be an activist. Harriet Tubman didn’t want to be an activist. But somebody has got to step up to the plate.”

A meeting with Dr. King 10 days before his assassination assured Carlos the boycott was the right thing to do. Carlos met with King, Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young at the Americana Hotel in New York. King pledged his support for the boycott, Carlos said, adding this his reasoning was that Black’s absence would deal a blow to the Games.

“If we refused to go … it would reach out to the end of the world that we were missing in action,” Carlos said.

Instead of boycotting the Games entirely, athletes used different forms of protests. Some athletes wore wooden bead necklaces to condemned lynches. Other wore black socks to denounce poverty. But the black-glove was representative of the Black race, Carlos explained, noting that for the first time the Games were broadcast in Technicolor.

“We wore the black gloves because we wanted it to be no misinterpretation as to whom we represented when we say powerful Black people,” Carlos explained, noting that the clenched fist showed unity and the true grit of Black people when they come together.

However, that gesture came at great cost to Carlos and his family. His wife lost her military job working for a five-star general and could not find another. His brothers were discharged from the military three days after the black fist salute.

Carlos sunk into a deep depression because he could not find work. The pressure became too much for his first wife, who later committed suicide. Even Carlos’ medals were threatened to be take away from him.

Carlos said he earned his medal by qualifying for a spot on the Olympic team and competing against the world to win bronze.

“I accomplished that goal,” he said. “You didn’t give me a medal. I don’t want you guys to think they give you something. You earn it. How can they take what you earn.”

Carlos reflected on the Vancouver Winter Olympics. He praised south side native Shani Davis for dominating a sport that has little respect for him. Davis won gold in the 1,000 meter speed skating event and silver in the 1,500 race.

“Not only is he a gifted young man, but he is a committed Black man,” Carlos said, noting that he cannot image the “hell” Davis must endure while competing in the Winter Olympics.

“You know the hell it was for me to go to the Summer Olympics competing as a Black man. Imagine how it is for a Black man competing in the Winter Olympic. Imagine the cynicism that he has to deal with everyday.”

He called Davis a hero, but Carlos contends that once Davis’ time in the spotlight wanes, “they are going to kick Shani to the curb.”

(This article first appeared in the Chicago Crusader newspaper)

Be the first to comment on "1968 Olympian reflects on moment that change the world"